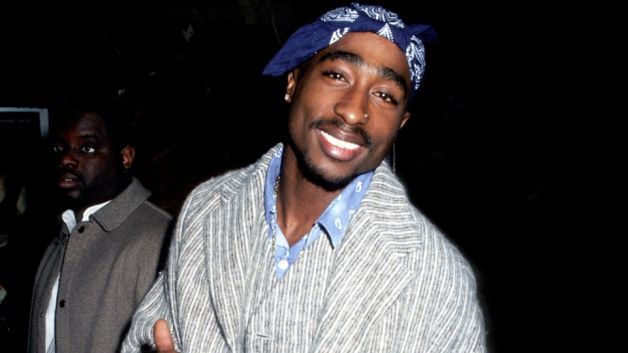

Tupac Amaru Shakur, rapper, actor, activist, thug, poet, rebel, and visionary, born Lesane Parish Crooks, June 16, 1971 – September 13, 1996, in East Harlem, New York.

Better known by his stage name 2Pac and by his alias Makaveli, was an American rapper and actor. He is widely considered to be one of the most influential rappers of all time.

Much of Shakur’s work has been noted for addressing contemporary social issues that plagued inner cities, and he has often been considered a symbol of activism against inequality.

Shakur was born in Manhattan, a borough of New York City, but relocated to Baltimore, Maryland in 1984 and then the San Francisco Bay Area in 1988.

He moved to Los Angeles in 1993 to further pursue his music career. By the time he released his debut album 2Pacalypse Now in 1991, he had become a central figure in West Coast hip hop, introducing social issues to the genre at a time when gangsta rap was dominant in the mainstream.

Shakur achieved further critical and commercial success with his follow-up albums Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z… (1993) and Me Against the World (1995).

In 1995, Shakur served eight months in prison on sexual assault charges, but was released after agreeing to sign with Marion “Suge” Knight’s label Death Row Records in exchange for Knight posting his bail.

Following his release, Shakur became heavily involved in the growing East Coast–West Coast hip hop rivalry.[6] His double-disc album All Eyez on Me (1996) was certified Diamond by the RIAA.

On September 7, 1996, Shakur was shot four times by an unknown assailant in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada; he died six days later and the gunman was never captured.

Shakur’s friend-turned-rival, The Notorious B.I.G., was at first considered a suspect due to the pair’s public feud, but was also murdered in another drive-by shooting six months later in Los Angeles, California. Five more albums have been released since Shakur’s death, all of which have been certified platinum in the United States.

Shakur is one of the best-selling music artists of all time, having sold over 75 million records worldwide. In 2002, he was inducted into the Hip-Hop Hall of Fame. In 2017, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

Rolling Stone named Shakur in its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.

Outside music, Shakur also found considerable success as an actor, with his starring roles as Bishop in Juice (1992), Lucky in Poetic Justice (1993) where he starred alongside Janet Jackson, Ezekiel in Gridlock’d (1997), and Jake in Gang Related (1997), all of which garnered praise from critics.

Personal life

Tupac Amaru Shakur was born on June 16, 1971, in East Harlem in New York City. While born Lesane Parish Crooks, he was renamed, at age one, after Túpac Amaru II (the descendant of the last Incan ruler, Túpac Amaru), who was executed in Peru in 1781 after his failed revolt against Spanish rule.

Amsterdam News wrote He was enrolled in the 127th Street Repertory Ensemble at age 12, taking on his first major role with the accomplished acting troupe in a 1984 production of “A Raisin in the Sun” at the Apollo Theater.

Shakur’s mother explained, “I wanted him to have the name of revolutionary, indigenous people in the world. I wanted him to know he was part of a world culture and not just from a neighborhood.”

Shakur had an older stepbrother, Mopreme “Komani” Shakur, and a half-sister, Sekyiwa, two years his junior.

His parents, Afeni Shakur—born Alice Faye Williams in North Carolina—and his birth father, Billy Garland, had been active Black Panther Party members in New York in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

His parents, Afeni Shakur—born Alice Faye Williams in North Carolina—and his birth father, Billy Garland, had been active Black Panther Party members in New York in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Panther heritage

A month before Shakur’s birth, his mother Afeni was tried in New York City as part of the Panther 21 criminal trial. She was acquitted of over 150 charges.

Other family members who were involved in the Black Panthers’ Black Liberation Army were convicted of serious crimes and imprisoned, including Shakur’s stepfather, Mutulu Shakur, who spent four years among the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives.

Mutulu Shakur was apprehended in 1986 and subsequently convicted for a 1981 robbery of a Brinks armored truck, during which police officers and a guard were killed.

Shakur’s godfather, Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt, a high-ranking Black Panther, was convicted of murdering a school teacher during a 1968 robbery.

His sentence was overturned when it was revealed that the prosecution had hidden evidence that he was in a meeting 400 mi away at the time of the murders.

School years

In 1984, Shakur’s family moved from New York City to Baltimore, Maryland. He attended eighth grade at Roland Park Middle School, then two years at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. On transfer to the Baltimore School for the Arts, he studied acting, poetry, jazz, and ballet.

He performed in Shakespeare’s plays—depicting timeless themes, now seen in gang warfare, he would recall—and as the Mouse King role in The Nutcracker ballet. With his friend Dana “Mouse” Smith as beatbox, he won competitions as reputedly the school’s best rapper.

Also known for his humor, he could mix with all crowds. As a teen, he listened to musicians including Kate Bush, Culture Club, Sinéad O’Connor, and U2.

At Baltimore’s arts high school, Shakur befriended Jada Pinkett, who would become a subject of some of his poems. After his death, she would call him “one of my best friends.

He was like a brother. It was beyond friendship for us. The type of relationship we had, you only get that once in a lifetime.” Upon connecting with the Baltimore Young Communist League USA, Shakur dated the daughter of the director of the local chapter of the Communist Party USA.

In 1988, Shakur moved to Marin City, California, a small, impoverished community, about 5 miles north of San Francisco. In nearby Mill Valley, he attended Tamalpais High School, where he performed in several theater productions.

Later relations

In Shakur’s adulthood, he continued befriending individuals of diverse backgrounds. His friends would range from Mike Tyson and Chuck D to Jim Carrey and Alanis Morissette, who in April 1996 said that she and Shakur were planning to open a restaurant together.

Shakur briefly dated Madonna in 1994. On April 29, 1995, Shakur married his then-girlfriend Keisha Morris, a pre-law student.

The marriage was annulled ten months later. In a 1993 interview published in The Source, Shakur berated record producer Quincy Jones for his interracial marriage to actress Peggy Lipton.

Their daughter Rashida Jones responded with an irate open letter. Years later, Shakur apologized to her sister Kidada Jones, who he was dating at the time of his death in 1996.

Music career

In January 1991, Shakur debuted under the stage name 2Pac on rap group Digital Underground’s single “Same Song.” The song was featured on the soundtrack of the 1991 film Nothing but Trouble.

His first two solo albums, 2Pacalypse Now (1991) and Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z… (1993), preceded Thug Life: Volume 1 (1994), the only album with his side group Thug Life. Rapper/producer Stretch guests on the three albums.

Here is a rare video of 2Puc in his old neighborhood in East Harlem:

2Pac’s third solo album, Me Against the World (1995), features rap clique Dramacydal, reshaping as Outlawz on 2Pac’s fourth solo album, and last in his lifetime, All Eyez on Me (1996).

At the time of his death, another solo album was already finished. The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996), under the stage name Makaveli, was recorded in one week in August 1996, whereas later posthumous albums are archival productions.

Later posthumous albums are R U Still Down? (1997), Greatest Hits (1998), Still I Rise (1999), Until the End of Time (2001), Better Dayz (2002), Loyal to the Game (2004), Pac’s Life (2006).

Beginnings: 1989–1991

Shakur began recording using the stage name MC New York in 1989. That year, he began attending the poetry classes of Leila Steinberg, and she soon became his manager. Steinberg organized a concert for Shakur and his rap group Strictly Dope.

Steinberg managed to get Shakur signed by Atron Gregory, manager of the rap group Digital Underground. In 1990, Gregory placed him with the Underground as a roadie and backup dancer.

Under the stage name 2Pac, he debuted on the group’s January 1991 single “Same Song,” leading the group’s January 1991 EP titled This Is an EP Release, while 2Pac appeared in the music video.

It also went on the soundtrack of the February 1991 movie Nothing but Trouble, starring Dan Aykroyd, John Candy, Chevy Chase, and Demi Moore.

Rising star: 1992–1993

2Pac’s debut album, 2Pacalypse Now—alluding to the 1979 film Apocalypse Now—arriving in November 1991, would bear three singles. Some prominent rappers—like Nas, Eminem, Game, and Talib Kweli—cite it as an inspiration.

Aside from “If My Homie Calls,” the singles “Trapped” and “Brenda’s Got a Baby” poetically depict individual struggles under socioeconomic disadvantage.

But once a Texas defense attorney, with a young client who had shot a state trooper, rationalized the defendant had been listening to the album, which touches upon police brutality, controversy ensued.

US Vice President Dan Quayle partially reacted, “There’s no reason for a record like this to be released. It has no place in our society.” Tupac, finding himself misunderstood, explained, in part, “I just wanted to rap about things that affected young Black males.

When I said that, I didn’t know that I was gonna tie myself down to just take all the blunts and hits for all the young Black males, to be the media’s kicking post for young Black males.”

In any case, 2Pacalypse Now was certified Gold, half a million copies sold. Altogether, the album sits well within the context of socially conscious rap, addressing urban Black concerns still prevalent in rap to this day.

2Pac’s second album, Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z…, arrived in February 1993. A critical and commercial advance, it debuted at No. 24 on the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200.

An overall more hardcore album, it emphasizes Tupac’s sociopolitical views and has a metallic production quality. It features Ice Cube, the famed primary creator of N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police,” who, in his own solo albums, had newly gone militantly political, along with L.A.’s original gangsta rapper, Ice-T, who in June 1992 had sparked controversy with his band Body Count’s track “Cop Killer”.

In fact, in its vinyl release, side A, tracks 1 to 8, is labeled the “Black Side,” while side B, tracks 9 to 16, is the “Dark Side.”

Nonetheless, the album carries the single “I Get Around,” a party anthem featuring Digital Underground’s Shock G and Money-B, which would render 2Pac’s popular breakthrough, reaching No. 11 on the pop singles chart, the Billboard Hot 100.

And it carries the optimistic compassion of another hit, “Keep Ya Head Up,” an anthem for women empowerment.

This album would be certified platinum, with a million copies sold. As of 2004, among 2Pac albums, including of posthumous and compilation albums, the Strictly album would be 10th in sales, about 1 366 000 copies.

Stardom: 1994–1995

In late 1993, Shakur formed the group Thug Life with Tyrus “Big Syke” Himes, Diron “Macadoshis” Rivers, his stepbrother Mopreme Shakur, and Walter “Rated R” Burns.

Thug Life released its only album, Thug Life: Volume 1, on October 11, 1994, which is certified Gold. It carries the single “Pour Out a Little Liquor”, produced by Johnny “J” Jackson, who would also produce much of Shakur’s album All Eyez on Me. Usually, Thug Life performed live without Tupac. The track also appears on the 1994 film Above the Rim’s soundtrack.

But due to gangsta rap being under heavy criticism at the time, the album’s original version was scrapped, and the album redone with mostly new tracks. Still, along with Stretch, Tupac would perform the first planned single, “Out on Bail,” which was never released, at the 1994 Source Awards.

2Pac’s third album, arriving in March 1995 as Me Against the World, is now hailed as his magnum opus, and commonly ranks among the greatest, most influential rap albums. The album sold 240,000 copies in its first week, setting a then-record for highest first-week sales for a solo male rapper.

The lead single, “Dear Mama,” arrived in February with the B side “Old School.” The album’s most successful single, it topped the Hot Rap Singles chart, and peaked at No. 9 on the pop singles chart, the Billboard Hot 100. In July, it was certified Platinum. It ranked No. 51 on the year-end charts.

The second single, “So Many Tears,” released in June, reached No. 6 on the Hot Rap Singles chart and No. 44 on Hot 100. August brought the final single, “Temptations,” reaching No. 68 on the Hot 100, No. 35 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks, and No. 13 on the Hot Rap Singles.

At the 1996 Soul Train Music Awards, Tupac won for best rap album.[74] In 2001, it ranked 4th among his total albums in sales, with about 3 524 567 copies sold in the US.

Superstardom: 1995–1996

While imprisoned from February to October 1995, Tupac wrote only one song, he would say.

Rather, he took to political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli’s treatise The Prince and military strategist Sun Tzu’s treatise The Art of War. And on Tupac’s behalf, his wife Keisha Morris communicated to Suge Knight of Death Row Records that Tupac, in dire straits financially, needed help, his mother about to lose her house. In August, after sending $15,000 for her, Suge began visiting Tupac in prison.

In one of his letters to Nina Bhadreshwar, recently hired to edit a planned magazine, Death Row Uncut, Tupac discusses plans to start a “new chapter.” Eventually, music journalist Kevin Powell would say that Shakur, once released, more aggressive, “seemed like a completely transformed person.”

2Pac’s fourth album, All Eyez on Me, arrived on February 13, 1996. Of two discs, it basically was rap’s first double album – meeting two of the three albums due in Tupac’s contract with Death Row – and bore five singles while perhaps marking the peak of 1990s rap. With standout production, the album has more party tracks and often a triumphant tone.

As 2Pac’s second album to hit No. 1 on both the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200, it sold 566,000 copies in its first week and was it was certified 5× Multi-Platinum in April. “How Do U Want It” as well as “California Love” reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

At the 1997 Soul Train Awards, it won in R&B/Soul or Rap Album of the Year. At the 24th American Music Awards, Tupac won Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Artist. The album was certified 9× Multi-Platinum in June 1998, and 10× in July 2014.

Tupac’s fifth and final studio album, The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, commonly called simply The 7 Day Theory, was released under a newer stage name, Makaveli.

The album had been created in seven days total during August 1996. The lyrics were written and recorded in three days, and mixing took another four days. In 2005, MTV.com ranked The 7 Day Theory at No. 9 among hip hop’s greatest albums ever, and by 2006 a classic album.

Its singular poignance, through hurt and rage, contemplation and vendetta, resonates with many fans. But according to George “Papa G” Pryce, Death Row Records’ then director of public relations, the album was meant to be “underground,” and “was not really to come out,” but, “after Tupac was murdered, it did come out.” It peaked at No. 1 on Billboard’s Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and on the Billboard 200, with the second-highest debut-week sales total of any album that year.

On June 15, 1999, it was certified 4× Multi-Platinum.

Film career

Tupac’s first film appearance was in the 1991 film Nothing but Trouble, a cameo by the Digital Underground. In 1992, he starred in Juice, where he plays the fictional Roland Bishop, a militant and haunting individual. Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers calls him “the film’s most magnetic figure.”

Then, in 1993, Tupac starred alongside Janet Jackson in John Singleton’s romance film, Poetic Justice. Tupac then played another gangster, the fictional Birdie, in Above the Rim. Soon after Tupac’s death, three more films starring him were released, Bullet (1996), Gridlock’d (1997), and Gang Related (1997).

Director Allen Hughes had cast Tupac as Sharif in the 1993 film Menace II Society, but replaced him once Tupac assaulted him on set due to a discrepancy with the script.

Nonetheless, in 2013, Hughes appraises that Tupac would have outshone the other actors, “because he was bigger than the movie.”

For the lead role in the eventual 2001 film Baby Boy, a role played by Tyrese Gibson, director John Singleton originally had Tupac in mind.

Ultimately, the set design includes in the protagonist’s bedroom a Tupac mural, and the film’s score includes the 2Pac song “Hail Mary.”

Criminal and civil cases

1991 Oakland Police Department lawsuit

In October 1991, Shakur filed a $10 million lawsuit against the Oakland Police Department for allegedly brutalizing him over jaywalking. The case was settled for about $43,000.

Shooting of Qa’id Walker-Teal

On August 22, 1992, in Marin City, Shakur performed outdoors at a festival. For about an hour after the performance, he signed autographs and posed for photos.

A conflict broke out and Shakur allegedly drew a legally carried Colt Mustang but dropped it on the ground.

Shakur claimed that someone with him then picked it up when it accidentally discharged. About 100 yards (90 meters) away in a schoolyard, Qa’id Walker-Teal, a boy aged 6 on his bicycle, was fatally shot in the forehead.

Police matched the bullet to a .38-caliber pistol registered to Shakur.

His stepbrother Maurice Harding was arrested, but no charges were filed. Lack of witnesses stymied prosecution.

In 1995, Qa’id’s mother filed a wrongful death suit against Shakur, settled for about $300,000 to $500,000.

Shooting two policemen

In October 1993, in Atlanta, Mark Whitwell and Scott Whitwell, two brothers who were both off-duty police officers, were out celebrating with their wives after one of them had passed the state’s bar examination. Drunk, the officers were crossing the street when a passing car carrying Shakur allegedly almost struck them.

The Whitwells, later found to have stolen guns, argued with the car’s occupants.

When a second car arrived, the Whitwells ran away, as Shakur shot one officer in the buttocks and the other in the leg, back, or abdomen. Shakur was charged in the shooting. Mark Whitwell was charged with firing at Shakur’s car and later with making false statements to investigators.

Prosecutors ultimately dropped all charges against both parties.

Both brothers filed civil suits against Shakur; Mark Whitwell’s was settled out of court, while Scott Whitwell’s $2 million lawsuits resulted in a default judgment entered against the rapper’s estate.

Assault convictions

On April 5, 1993, charged with felonious assault, Shakur allegedly threw a microphone and swung a baseball bat at rapper Chauncey Wynn, of the group M.A.D., at a concert at Michigan State University.

On September 14, 1994, Shakur pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and was sentenced to 30 days in jail, twenty of them suspended, and ordered to 35 hours of community service.

Slated to star as Sharif in the 1993 Hughes Brothers’ film Menace II Society, Shakur was replaced by actor Vonte Sweet after allegedly assaulting one of the film’s directors, Allen Hughes.

In early 1994, Shakur served 15 days in jail after being found guilty of the assault. The prosecution’s evidence included a Yo! MTV Raps interview where Shakur boasts that he had “beat up the director of Menace II Society.”

Sexual assault conviction

In November 1993, Shakur and three other men were charged in New York with sexually assaulting a woman in his hotel room.

The woman, Ayanna Jackson, alleged that after consensual oral sex in his hotel room, she returned a later day, but then was raped by him and other men there.

Interviewed on The Arsenio Hall Show, Shakur said he was hurt that “a woman would accuse me of taking something from her.”

On December 1, 1994, Shakur was convicted of first-degree sexual abuse, but acquitted of associated sodomy and gun charges.

In February 1995, he was sentenced to 18 months to 4+1⁄2 years in prison by a judge who decried “an act of brutal violence against a helpless woman.”

On October 12, 1995, pending judicial appeal, Shakur was released from Clinton Correctional Facility,[29] once Suge Knight, CEO of Death Row Records, arranged for posting of his $1.4 million bond.

On April 5, 1996, Shakur was sentenced to 120 days in jail for violating his release terms by failing to appear for a road cleanup job, but on June 8, his sentence was deferred via appeals pending in other cases.

New York scene 1990s

In 1991, 2Pac debuted on a new record label, Interscope Records, that knew little about rap music. Until that year, Ruthless Records, formed during 1986 in Los Angeles county’s Compton city, had prioritized rap, and its group N.W.A had led gangsta rap to platinum sales, but N.W.A’s lyrics, outrageously violent and misogynist, precluded mainstream breakthrough.

On the other hand, also specializing in rap, Profile Records, in New York City, had a mainstream, pop breakthrough, Run-DMC’s “Walk This Way”, in 1986.

In April 1991, N.W.A disbanded via Dr. Dre’s departure to, with Suge Knight, launch Death Row Records, in Los Angeles city. With its very first two albums, Death Row became the first record label both to prioritize rap and to regularly release mainstream, pop hits with it.

Released by Death Row in late 1992, Dre’s The Chronic—its “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang” ubiquitous on pop radio and “Let Me Ride” winning a Grammy—was trailed in late 1993 by Snoop’s Doggystyle.

Gangsta rap, no less, these albums and more propelled the West Coast, for the first time, ahead of New York to rap’s center stage. But meanwhile, in 1993, Andre Harrell of Uptown Records, in New York, fired his star A&R man, Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, later “P. Diddy.”

Puffy, while leaving behind his standout projects Jodeci and Mary J. Blige—two R&B acts—took to his own, new record label, Bad Boy Records, the promising gangsta rapper Biggie Smalls, soon also known as The Notorious B.I.G. His debut album, released in late 1994 as Ready to Die, promptly returned rap’s spotlight to New York.

Rap world

Stretch and Live squad

In 1988, Randy “Stretch” Walker, along with his brother, dubbed Majesty, and a friend debuted with an EP as rap group and production team, Live Squad, in the Queens borough of New York City.

Tupac’s early days with Digital Underground made his acquaintance with Stretch, who featured on a track of the Digital Underground’s 1991 album Sons of the P. Becoming fast friends, Tupac and Stretch recorded and performed together often.

Stretch as well as Live Squad contributed tracks on 2Pac’s first two albums, first November 1991, then February 1993, and on 2Pac’s side group Thug Life’s only album of September 1994.

The end of Tupac’s and Stretch’s friendship in late 1994 surprised the New York rap scene. The next 2Pac album, released in March 1995, lacks Stretch, and 2Pac’s album after that, released in February 1996, has lines suggesting Stretch’s impending death for betrayal.

No objective evidence would publicly emerge to tangibly incriminate Stretch in the gun attack on Tupac, while with Stretch and two others, at about 12:30 am on November 30, 1994.

In any case, after a Live Squad production session for the second album of Queens rapper Nas, Stretch’s vehicle was chased while receiving fatal gunfire at about 12:30 am on November 30, 1995.

Biggie and Junior M.A.F.I.A.

During 1993 and 1994, the Biggie Smalls guest verses on several singles, often R&B, like Mary J. Blige’s “What’s the 411? Remix,” set high expectations for his debut album.

The perfectionism of Puffy, still forming his Bad Boy label, extended its recording to 18 months. In 1993, visiting Los Angeles, Biggie asked a local drug dealer for an introduction to Tupac, who then welcomed Biggie and Biggie’s friends to Tupac’s house and treated them to recreational activities. On later visits to Los Angeles, Biggie would stay at Tupac’s place. And when in New York, Tupac would go to Brooklyn and hang out with Biggie and his circle.

During this period, at his own live shows, Tupac would call Biggie onto stage to rap with him and Stretch. Together, they recorded the songs “Runnin’ from the Police” and “House of Pain.” Reportedly, Biggie asked Tupac to manage him, whereupon Tupac advised him that Puffy would make him a star.

Yet in the meantime, Tupac’s lifestyle was comparatively lavish, whereas Biggie appeared to continue wearing the same pair of boots for perhaps a year.

Tupac welcomed Biggie to join his side group Thug Life. Biggie would instead form his own side group, the Junior M.A.F.I.A., with his Brooklyn friends Lil’ Cease and Lil’ Kim, on Bad Boy.

Underworld

Despite the “weird” timing of Stretch’s shooting death, a theory implicates gunman Ronald “Tenad” Washington both here and in the 2002 murder of Run-DMC’s Jam Master Jay via, as the unverified theory speculates, Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff punishing the rap mentor for recording 50 Cent despite Supreme’s prohibition after this young rapper’s 1999 song “Ghetto Qu’ran” had mentioned activities of the Queens drug gang Supreme Team.

Supreme was a friend, rather, of Irv Gotti, cofounder of Murder Inc Records, whose rapper Ja Rule would vie among New York rappers after the March 1997 shooting death of Biggie, visiting Los Angeles.

Haitian Jack

By some accounts, the role Birdie, played by Shakur in the 1994 film Above the Rim, had been modeled on a New York underworld tough, Jacques “Haitian Jack” Agnant, a manager and promoter of rappers.

Reportedly, Shakur met him at a Queens nightclub, where, noticing him amid women and champagne, Shakur asked for an introduction.

Reportedly, Biggie advised Tupac to avoid him, but Tupac disregarded the warning.

In November 1993, in his Manhattan hotel room, Shakur received a woman’s return visit. Soon, she alleged sexual assault by him and three other men there: his road manager Charles Fuller, aged 24, one Ricardo Brown, aged 30, and a “Nigel,” later understood as Haitian Jack. In November 1994, Jack’s case was split off and closed via misdemeanor plea without incarceration.

In 2007, for shooting at someone, he would be deported. Yet in November 1994, A. J. Benza, in the New York Daily News, reported Tupac’s new disdain for Jack.

Jimmy Henchman

Through Haitian Jack, Tupac had met James “Jimmy Henchman” Rosemond. Another underworld figure formidable, Jimmy Henchman doubled as music manager.

Bryce Wilson’s Groove Theory was an early client. The Game as well as Gucci Mane were later clients. In 1994, a client lesser known, and signed to Uptown Records, was rapper Little Shawn, friend of Biggie and Lil’ Cease.

Eventually, Jack and Henchman would reportedly fall out, allegedly shooting at each other in Miami. And for his major drug trafficking, Henchman would be sent to prison on a life sentence. But in the early 1990s, Jack and Henchman reputedly shared interests, including a specialty of robbing and extorting music artists.

Shootings of Shakur

November 1994

On November 30, 1994, while in New York, Tupac was recording verses for a mixtape of Ron G. Tupac was repeatedly distracted by his beeper. It was music manager James “Jimmy Henchman” Rosemond, reportedly offering $7,000 for Tupac to stop by Quad Studios, in Times Square, that night to record a verse for his client Little Shawn.

Tupac was leery, but needing cash to offset steepening legal costs, took the gig. Tupac arrived with Stretch and one or two others. In the lobby, three men robbed and beat him at gunpoint; Tupac resisted and was shot. Shakur speculated that the shooting had been a set-up.

Three hours after surgery, against doctor’s advice, Shakur checked out of Bellevue Hospital Center. The next day, in a Manhattan courtroom bandaged in a wheelchair, he received the jury’s verdict in his ongoing criminal trial for a November 1993 sexual assault in his hotel room.

Convicted of three counts of sexual assault, he was acquitted of six other charges, including sodomy and gun charges.

In a 1995 interview with Vibe magazine, Shakur accused Sean Combs, Jimmy Henchman, and Biggie, among others, of setting up or being privy to the November 1994 robbery and shooting. Vibe alerted the names of the accused.

The accusations were significant to the East-West Coast rivalry in hip-hop, the accusation was because Sean Combs and Christopher Wallace were at Quad Studios at the time, and in 1995, months later, Combs and Wallace releasing the song “Who Shot Ya?”, whereas the song made no direct reference or naming of Shakur, Shakur took it as a mockery of his shooting and thought they could be responsible, so he released a (direct) diss song called “Hit ‘Em Up”, where he targeted Wallace, Combs, their record label, Junior M.A.F.I.A., and at the end of “Hit ‘Em Up”, he mentions rivals Mobb Deep and Chino XL.

In March 2008, Chuck Philips, in the Los Angeles Times, reported on the 1994 ambush and shooting. The newspaper later retracted the article since it relied partially on FBI documents later discovered forged, supplied by a man convicted of fraud.

In June 2011, convicted murderer Dexter Isaac, incarcerated in Brookyn, issued a confession that he had been one of the gunmen who had robbed and shot Shakur at Henchman’s order. Philips then named Isaac as one of his own, retracted article’s unnamed sources.

Death Row signs Shakur

During 1995, imprisoned, impoverished, and his mother about to lose her house, Tupac had his wife Keisha Morris get word to Marion “Suge” Knight, in Los Angeles, boss of Death Row Records. Reportedly, Tupac’s mother promptly received $15,000.

After an August visit to Clinton Correctional Facility in northern New York state, Suge traveled southward to New York City to join Death Row’s entourage to the 2nd Annual Source Awards ceremony.

Already reputed for strongarm tactics on the Los Angeles rap scene, Suge used his brief stage time mainly to belittle Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, boss of Bad Boy Entertainment, the label then leading New York rap scene, who routinely performed with his own artists.

Before closing with a brief comment of support for Tupac, Suge invited artists seeking the spotlight for themselves to join Death Row.

Eventually, Puff recalled that to preempt severe retaliation from his Bad Boy orbit, he had promptly confronted Suge, whose reply – that he had meant Jermaine Dupri, of So So Def Recordings, in Atlanta – was politic enough to deescalate the conflict.

Still, among the fans, the previously diffuse rivalry between America’s two mainstream rap scenes had instantly flared already. And while in New York, Suge visited Uptown Records, where Puff, under its founder Andre Harrell, had started in the music business through an internship.

Apparently without paying Uptown, Suge obtained the releases of Puff’s prime Uptown recruits Jodeci, its producer DeVante Swing, and Mary J. Blige, all then signing with Suge’s management company.

On September 24, 1995, at a party for Dupri in Atlanta at the Platinum House nightclub, a Bad Boy circle entered a heated dispute with Suge and Suge’s friend Jai Hassan-Jamal “Big Jake” Robles, a Bloods gang member and Death Row bodyguard.

According to eyewitnesses, including a Fulton County sheriff, working there as a nightclub bouncer, Puff had heatedly disputed with Suge inside the club, whereas several minutes later, outside the club, it was Puff’s childhood friend and own bodyguard, Anthony “Wolf” Jones, who had aimed a gun at Big Jake, fatally shot while entering Suge’s car.

The attorneys of Puff and his bodyguard both denied any involvement by their clients, while Puff’s added that Puff had not even been with his bodyguard that night. Over 20 years later, the case remains officially unresolved.

Yet immediately and persistently, Suge blamed Puff, cementing the enmity between the two bosses, whose two record labels dominated the rap genre’s two mainstream centers. In the late 1990s, Southern rap’s growth into the mainstream would dispel the East–West paradigm.

But in the meantime, in October 1995, violating his probation, Suge visited Tupac in prison again. Suge posted $1.4 million bonds. And with the appeal of his December 1994 conviction pending, Shakur returned to Los Angeles and joined Death Row.

On June 4, 1996, it released the 2Pac B side “Hit ‘Em Up.” In this venomous tirade, the proclaimed “Bad Boy killer” threatens violent payback on all things Bad Boy—Biggie, Puffy, Junior M.A.F.I.A., the company—and on any in New York’s rap scene, like rap duo Mobb Deep and obscure rapper Chino XL, who allegedly had commented against Shakur about the dispute.

Death

East Flamingo Road and Koval Lane, where the murder occurred On the night of September 7, 1996, Shakur was in Las Vegas, Nevada, to celebrate his business partner Tracy Danielle Robinson’s birthday and attended the Bruce Seldon vs. Mike Tyson boxing match with Suge Knight at the MGM Grand.

Afterward in the lobby, someone in their group spotted Orlando “Baby Lane” Anderson, an alleged Southside Compton Crip, whom the individual accused of having recently in a shopping mall tried to snatch his neck chain with a Death Row Records medallion.

The hotel’s surveillance footage shows the ensuing assault on Anderson. Shakur soon stopped by his hotel room and then headed with Knight to his Death Row nightclub, Club 662, in a black BMW 750iL sedan, part of a larger convoy.

At about 11 pm on Las Vegas Boulevard, bicycle-mounted police stopped the car for its loud music and lack of license plates.

The plates were found in the trunk and the car was released without a ticket. At about 11:15 pm at a stop light, a white, four-door, late-model Cadillac sedan pulled up to the passenger side and an occupant rapidly fired into the car.

Shakur was struck four times: once in the arm, once in the thigh, and twice in the chest with one bullet entering his right lung. Shards hit Knight’s head. Frank Alexander, Shakur’s bodyguard, was not in the car at the time. He would say he had been tasked to drive the car of Shakur’s girlfriend, Kidada Jones.

Shakur was taken to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada where he was heavily sedated and put on life support. In the intensive-care unit on the afternoon of September 13, 1996, Shakur died from internal bleeding. He was pronounced dead at 4:03 pm.

The official causes of death are respiratory failure and cardiopulmonary arrest associated with multiple gunshot wounds. Shakur’s body was cremated the next day.

Members of the Outlawz, recalling a line in his song “Black Jesus,” (although uncertain of the artist’s attempt at a literal meaning chose to interpret the request seriously) smoked some of his body’s ashes after mixing them with marijuana.

In 2002, investigative journalist Chuck Philips, after a year of work, reported in the Los Angeles Times that Anderson, a Southside Compton Crip, having been attacked by Suge and Shakur’s entourage at the MGM Hotel after the boxing match, had fired the fatal gunshots, but that Las Vegas police had interviewed him only once, briefly, before his death in an unrelated shooting.

Philips’s 2002 article also alleges the involvement of Christopher “Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace and several within New York City’s criminal underworld. Both Anderson and Wallace denied involvement, while Wallace offered a confirmed alibi. Music journalist John Leland, in the New York Times, called the evidence “inconclusive.”

In 2011, via the Freedom of Information Act, the FBI released documents related to its investigation which described an extortion scheme by the Jewish Defense League that included making death threats against Shakur and other rappers but did not indicate a direct connection to his murder.

Photo credits: 1) Wikipedia. 2-4) Wikipedia. 5) Youtube video. Story adapted from source.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Harlem World Magazine, 2521 1/2 west 42nd street, Los Angeles, CA, 90008, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact