Harlem, originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands, was founded by the Dutch on land that the Manahattans and Wickquaskeeks Indian tribes from the region resided.

This whole region is now almost the geographical heart of New York City.

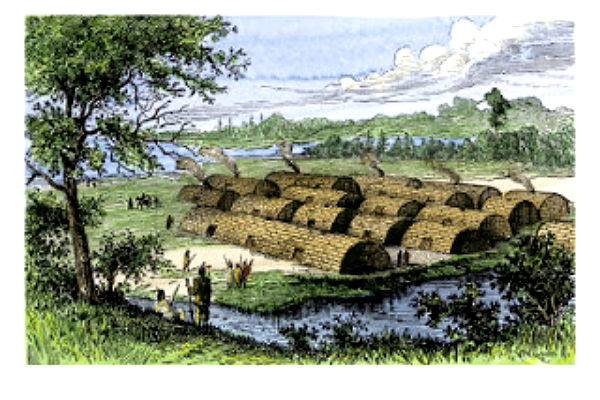

Patterned after similar villages in France and England, this little settlement of about 20 families received power to own, buy, sell, or distribute property, elect officers, assess members, build churches, hold court and govern itself in the exercise of authority common to corporate towns of the day.

Attempts at earlier settlement on the northern end of Manhattan Island had proved futile but began in earnest with the arrival of Hendrick (Henry) de Forest, his brother Isaac de Forest and their sister and brother-in-law, Rachel and Dr. Jean Mousnier De La Montagne, Franco-Dutch immigrants in 1636.

Hendrick and Isaack lost no time in seeking a favorable situation for a plantation. They came prepared to earn their living by raising tobacco, for which it was said the New Netherland soil of Manhattan Island “on account of its great fertility was considered well adapted.”

A stretch of rich bottomland in the northern part of the island was soon selected. This tract was called Muscoota (the flat land) by the Indians, who had doubtless already cleared and cultivated a considerable part of it. The Muscoota included all the Harlem River lowlands from Hellgate to High Bridge.

Hendrick promptly secured from Director Wouter van Twiller a grant of 100 morgens of land (about two hundred acres) on this fertile plain, extending “between the hills and the kill,” that is, from the high land known today as Morningside Heights to a little stream now called Harlem Creek, which ran in a southerly and easterly direction until it emptied into the Harlem River.

The northern boundary of the tract was at about 124th Street, while on the south it included the high land in Central Park at about 109th Street.

Near this latter boundary was a copious spring or, as the Dutch called it, a fonteyn, which still flows almost as it did then, a rippling brook with little waterfalls, until it empties into Harlem Mere in the northern part of the park.

Roughly speaking, between 3,000-4,000 acres, every foot of which is now extremely valuable, was granted to the Corporation—the Town of New Harlem—whose first settlers broke ground near the foot of 125th Street and the Harlem River on 14 Aug. 1658.

Erf (plural erven) was the Dutch name for a house-lot and morgen (two acres) meaning farm-lots. An owner of erf and morgen-rights was entitled to draw as many acres of the undivided common lands as he held of these rights.

Dr. Montagne, whose name has been variously misspelled, a descendant of French Huguenots who–like many other Nieuw Netherlands settlers–had fled persecution to settle in Holland.

Jean Mousnier de la Montagne from the time of his arrival in Nieuw Netherland signed himself simply La Montagne, though he was often called Johannes La Montagne or Montanye, and the name was frequently pronounced according to the latter spelling.

From Gov. William Kieft, Dr. Montagne obtained a grant of the land on which he had settled and expressed a sense of gratitude for the contrasting peace of his new home in calling it Quiet Dale or Vredendal.

The land which Montagne occupied soon became known as Montagne’s Flat. The tract, divided by the present line of St. Nicholas Avenue, ran from 109th Street to 124th Street and contained about 200 acres.

Shortly afterward, former director Wouter Van Twiller became interested in the Harlem district and settled on Ward’s Island. His friend Jacobus Van Curler pre-empted the flat opposite Ward’s Island known as the Otterspoor, a name signifying “otter tracks.”

This was afterwards sold to Coenraet Van Keulen, a New York merchant, and hence the name Van Keulen’s Hook, which clung to this part of the district for more than 100 years after Harlem’s founding.

With the ushering-in of spring, Van Curler finished his primitive dwelling and out-buildings on the northern bank of Montagne’s Creek and secured a stock of all things necessary for a well-regulated plantation of the day—domestic animals, farming tools, and a canoe for passing to and from New York.

At that time, and for a considerable time thereafter, there was no thought of reaching Nieuw Amsterdam except by water.

The success attending these early efforts in the rich soil of Muscoota had by this time spread abroad and had attracted the attention of a Danish capitalist, Capt. Jochem Pieter, who finally settled on the land above 125th Street.

His farm, which reached approximately to 150th Street along the Harlem River, was forever afterward known to the patentees as Jochem Pieter’s lots.

Jochem Pieter’s full name was Jochem Pietersen Kuyter. The Dutch, not unlike their American descendants, were quick to abbreviate names. Kuyter, therefore, was always known as Jochem Pieter.

When Jochem Pieter first made known his intention of coming to Manhattan, the authorities offered him the farm he subsequently occupied.

Pleased with their generosity, Jochem Pieter hired a ship, invited his friend Jonas Bronck to accompany him, stocked the vessel with fine Holstein cattle and, with the Pieter and Bronck families and numerous herdsmen, arrived in Nieuw Amsterdam in July 1639 and at once took up his residence on the banks of the Harlem.

Bronck, his associate, settled opposite in what is now Bronx Borough–to which he lent his name–and at once started to erect a stone house, covered with Dutch tiles, a barn, tobacco houses, and barracks.

When Hendrick De Forest died in July 1637, Dr. Montagne took charge of the widow’s plantation. He also saw to the proper harvesting of her crops and boarded with Van Curler while finishing the house and barn which his brother-in-law had started in the rough.

Dr. Montagne continued to look after the estate of his sister-in-law until the year following, when a former member of Van Twiller’s council, Andries Hudde, married the young widow De Forest.

Particularly noteworthy was this event, leading up to the first ground-brief, or land patent, which was issued relative to Harlem lands, “granting, transporting, ceding, giving over, and conveying, to Andries Hudde, his heirs and successors, now and forever” a site owned less than a generation later by the town of Harlem.

After his marriage, Hudde, wishing to visit Holland with his bride, engaged an overseer for the farm and applied to Director Kieft for a patent to avoid all questions of title to the property during his absence.

Hitherto no similar action had been taken, but Kieft, recognizing the value of the Harlem settlement as a protection against the Indians and recognizing also that settlers would not continue to dwell on and improve property where titles were insecure, inaugurated the custom of giving ground-briefs for Harlem farms, in course of improvement, by issuing the Hudde Patent, dated 20 July 1638.

By the time the newly-wedded pair reached Holland, however, their affairs on this side of the water were complicated by Dr. Montagne’s demand for the settlement of a debt of $400 due him for the management of the estate during the widowhood of Mrs. De Forest, now Mrs. Hudde.

The claim remaining unpaid, the farm was offered for sale for the benefit of the widow. At the auction which followed, Dr. Montagne bid for the property at 1,700 guilders, or about $680, which sum purchased not only the farm, but also the fixtures, house, barn, fences, farming tools, and wey schuyt (as the Dutch called the canoe), “domestic fowls, two goats, two milch cows and other cattle, and portions of the recent crops of tobacco and grain.”

Thus the claim to New Harlem’s land called Montagne’s Point and Montagne’s Flat became merged under one ownership, where it remained until the formation of the New Harlem Corporation.

Claes Cornelissen Swits, a New Yorker, leased the farm which Van Kuelen purchased from Van Curler. The terms of his lease were interesting, showing the progress made by the little Harlem colony in the three years of its existence.

The lease, which was executed on 25 Jan. 1639, included two span of horses, three cows, farming utensils and 12 schepels of grain in the ground, for which Swits was to pay rent in livestock and butter and one-eighth of all the grain “with which God shall bless the field.”‘

Dr. Montagne was yet to find, as did his neighbors, that this retreat was not so peaceful as it first seemed. The Native Americans lurked too near at hand.

Instead of the former quiet of the forest, the squeak of the ox-carts wheels and the swish of the scythes in the meadow now warned the Manahattans and Wickquaskeeks, the Indian tribes of the region, that civilization was soon to rob them of their beloved hunting grounds.

Despite Pieter Minuit’s purchase of the island and subsequent purchases of the Bronx and Westchester lowlands, the Native Americans became aggressive, declaring that $24 was an inadequate price for the whole of the island, and their tone became threatening.

Gov. Kieft added fuel to the smoldering fire of the Indians’ anger by attempting to levy a tax on the surrounding tribes. In vain did Dr. Montagne protest, but Kieft was vindictive. His demands being refused, he ordered an attack on the Raritan Indians.

Several were killed, and, in the words of Dr. Montagne, “a bridge had been built over which war was soon to stalk through the land.”

Swits was the first to fall in the trail of death that ensued. Kieft unwisely demanded the head of the assassin. New York’s Council not supporting him, however, no active measures were taken to capture the culprit.

Doubling their precautions, now that one of their numbers had been killed, the settlers along the Harlem returned to their crops and renewed their labors in the shadow of constant danger.

Kieft again contrived to blunder in his relations with the Indians and his blunders were always particularly costly to the little Harlem colony.

In the fall of the year, he ordered the slaughter of some harmless, unarmed Indians who had sought, at the fort, a refuge from their enemies, the Mohicans.

Immediately the Indians rose, thirsting for revenge and swarming like angry hornets from the forests, boldly attacked the Harlem outpost of Manhattan Island civilization, killed some of the settlers, and drove the remainder southward to New York.

Such attacks were repeated again and again in the next five years until Montagne and his neighbors were ruined, their cattle killed, their well-filled barns burned, their gardens and fences uprooted, their fields laid waste; and again the forest’s silence was broken only by the cry of birds or the twang of the bow.

Photo credit: 1) The Wickquaskeeks. 2) Early Harlem in Manhattan Island Native American village. 3) Waterfall at 109th Street, Montanye’s Fonteyn in the early 20th century. 4) “Thought they only granted hunting rights,” Indians and the Settlers 5) Declaration of Cornelis Cornelissen and Others Regarding the Destruction of a House by the Indians, 1644. Reported by Maddies Ancestor Search.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Harlem World Magazine, 2521 1/2 west 42nd street, Los Angeles, CA, 90008, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact