Imprisoned by her husband, “little Ronnie Bennett from Spanish Harlem” has now turned her tale of survival into a stage show.

Where else to meet Ronnie Spector, the Sixties girl-group icon, but in the ladies loos? The woman who once boasted the Rolling Stones as her opening act is primping her hair in the mirror, an enormous and fragrant mane bigger than her torso.A telltale pack of Marlboro cigarettes rests on the windowsill.

She’s 70 years old and the sexiest person I’ve ever interviewed, an irrepressible wiggle in her hips, throaty giggles bubbling out of her. There’s so much vivacity to her that it seems impossible that she could have been shut away in one of the most nightmarish marriages in the history of show business as Phil Spector’s wife.

Having divorced, remarried, and endured a 15-year legal battle against her ex-husband over unpaid royalties which she finally won, she’s now as adored for her chutzpah as for her hits. Beyond the Beehive, which has its British premiere in London this weekend, is her life story on stage – a mix of songs and stories from her career – and she seems as thrilled as a teenager to be performing again.

“People are very interested in all my ins and outs and ups and downs and Beatles and Stones,” she says, settling into a sofa in a Manhattan rehearsal studio on a snowy Thursday night. “The first time we went to the UK it meant everything to us because we knew we had made it.”

When the Ronettes landed in London in 1964 with their tight harmonies and even tighter dresses, there was hysteria and the 20-year-old lead singer with the remarkable voice, who was already dating Phil Spector, had Keith Richards and John Lennon chasing after her.

“It was very scary, because I really liked John Lennon and I was saying, ‘Oh my god I’ve got to think about Phil’. John really had a big crush on me. I’ll never forget sitting on the windowsill, looking out on the lights and I said, ‘London is so beautiful’. And he said, ‘you sure are’, because he was looking at me. It made me want to cry, because I really felt such a star then. That moment, I knew I’d made it.

But as she began to realise her potential, so did her possessive boyfriend and he was as horrified as she was elated. Incensed not just by the attention of the Stones and the Beatles, but by the hordes of adoring young men the Ronettes drew wherever they went, after their marriage in 1968, Phil Spector pulled her from the limelight and imprisoned her in his California mansion. The only time Spector allowed her to leave was once a month, “to go get my feminine stuff, if you catch my drift”. If she was gone longer than 20 minutes he’d send a bodyguard.

The last year of my marriage I didn’t talk at all. Because if I said anything he’d yell at me, so why say anything. I was a scared little girl from Spanish Harlem living in this mansion with five servants, not knowing what to do with any of it. I cried every night I was married.

He’d scream at her so violently, she says, that she eventually became mute: “The last year of my marriage I didn’t talk at all. Because if I said anything he’d yell at me, so why say anything. I was a scared little girl from Spanish Harlem living in this mansion with five servants, not knowing what to do with any of it. I cried every night I was married.”

Of all the privations he subjected her to, not singing was the hardest: “I’d think, ‘Why aren’t I on that stage, where’s the audience?’ I was craving it.” Her voice crumples with emotion and I make a gesture of sympathy. “It’s OK,” she says, “I go through it every night when I do my show. I get emotional, I can’t help it.”

Finally, in the summer of 1972, her worried mother paid a visit. “She said, ‘honey, you’re going to die here’. She knew.” The two of them stayed up for three days and nights meticulously planning her escape. Spector often hid her shoes so she left barefoot in order to not to arouse his suspicions. His parting words (not that he knew it) were directed to her mother: “Now Mrs Bennett don’t let Veronica step on anything sharp.”

Veronica Yvette Bennett was born in Spanish Harlem in 1943 to an Irish father and half African-American, half Cherokee mother with an enormous extended family.

Veronica Yvette Bennett was born in Spanish Harlem in 1943 to an Irish father and half African-American, half Cherokee mother with an enormous extended family.

She remembers being eight and singing in the lobby of her grandmother’s building, whose high ceilings produced a gratifying echo. More gratifying, though, was the response from her cousins.

“They were going insane – ‘Ronnie, Ronnie, you’re the one, you’ve got it!’ And I did have it. But my parents couldn’t afford to send me to singing lessons.”

Instead, she’d go home from school and play records – Frankie Lymon, Frankie Valli, The Schoolboys – and learn them in their entirety. When her parents realised she was doing this every night rather than any homework her mother struck a deal.

“She said, ‘I’m going to put you at the Apollo. And then we’ll see how good you are.’ ”

The legendary Harlem music hall was owned by Frank Schiffman, whose son, Bobby, happened to have a crush on her mother who worked as a waitress in a café next door. Through him, she was able to get Ronnie, her sister Estelle and her cousin Nedra a slot.

The legendary Harlem music hall was owned by Frank Schiffman, whose son, Bobby, happened to have a crush on her mother who worked as a waitress in a café next door. Through him, she was able to get Ronnie, her sister Estelle and her cousin Nedra a slot.

Apollo audiences were notoriously unforgiving – egg hurling was de rigueur. Not that night, though. They loved Ronnie’s voice and, as she says: “That was my key – I knew I was good.”

Eventually, they were signed to Colpix Records in 1961 as the Darling Sisters. An aunt made their first outfits – dresses fringed on the back, “so when we turned our backs to the audience and shook like that”, she wiggles in her seat, “the crowd would go nuts”.

A radio hit, however, eluded them. That changed when, with one audacious phone call to his office, Estelle got them signed to Phil Spector’s Philles label in 1963.

There are some songs that sound as though they’ve been dispatched, fully formed and perfect from some higher place. Be My Baby, the Ronettes’ first hit that year – a song that Brian Wilson claims to have listened to 100 times every day – remains indelible.

“I’ll tell you the truth,” she says, “I never get sick of singing,” – and the music bursts out of her – “be my little baby!” “I mean, that’s me!”

Ronnie was 17 and Spector was 24 when they met. I ask her what she fell in love with.

“First,” she says, “I fell in love with his coolness. He was very cool. Always had one hand in his pocket. And he had a cute butt. I loved his tush, he had the cutest tush. The way he handled the band – here’s a guy, 24 years old, yet he’s telling married men with children what to do? That turned me on so much. I fell in love with that power.”

They also made an incredible musical partnership. The dense arrangements and echo-chambered ensembles that formed Spector’s revolutionary “Wall of Sound” production technique bestowed sugar-sweet teenage love songs with the grandeur of orchestral symphonies. Combined with the ragged plangency of Ronnie’s voice, the result was irresistible.

“When he would write those songs and I’d be sitting on the piano next to him… oh, my heart… It was magic.”

Listening to the lyrics now, such as “Will he be good to me, wonder if he’ll love me for ever and ever” from 1964’s I Wonder, it’s hard in hindsight to resist their poignancy.

Five years ago, Phil Spector was convicted of murdering the actor and model Lana Clarkson, shot dead in his home in 2003. I ask Ronnie how it feels to know he’s behind bars.

She gives my leg a little slap, leans in, and with conspiratorial glee says: “It feels wonderful! – The more he tried to destroy me, the stronger I got. It made me think, ‘How dare you, you don’t own me’.

“Years ago we were like creations of genius men. We were little Stepford singers, interchangeable, one from column A, two from column B. We were seen as employees, not artists. I can’t speak for all the girls but I always saw myself as an artist. That’s why I think I’m still alive – to say we girls have to stick up for ourselves.”

Half a century on from being a teen idol, she’s an icon of survival, which is perhaps why audiences young and old tend to sob through her shows. In her mind, though, she remains “little Ronnie Bennett from Spanish Harlem”.

“I’m just a regular girl who loves the stage and who loves to sing,” she says. “That’s all I am. I’m not an ‘icon’ or ‘legend’ – I don’t understand those words.” She trots off, perhaps to do her hair, perhaps to sneak another of those Marlboro Reds. While she’s gone, Jonathan, her manager and husband of 30 years, takes my hand, shakes it soberly and looks me in the eye. “She is,” he says, “an indomitable spirit.”

Ronnie herself sums it with a little more levity on her return. “It was a b—-,” she beams, “but I keep on trucking.”

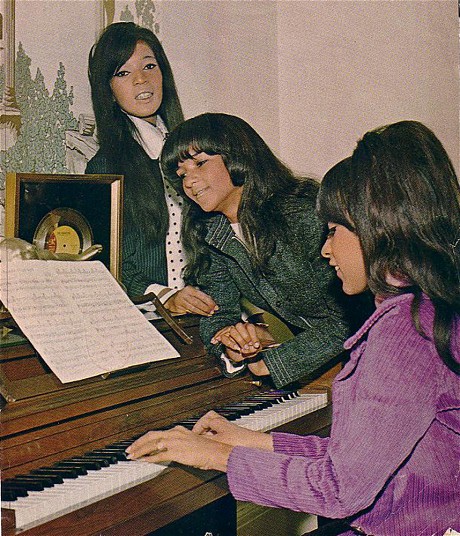

Photo credit: Harlem nights: The Ronettes in their Harlem apartment in New York in 1966 with Ronnie Spector at the piano (Kevin Dilworth).

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Harlem World Magazine, 2521 1/2 west 42nd street, Los Angeles, CA, 90008, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact