Juneteenth (a portmanteau of June and nineteenth; also known as Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, Liberation Day, and Emancipation Day) is a holiday celebrating the liberation of slaves in the United States. Originating in Texas, it is now celebrated annually on the 19th of June throughout the United States, with varying official recognition. Specifically, it commemorates Union army general Gordon Granger announcing federal orders in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, proclaiming that all people held as slaves in Texas were free.

The Emancipation Proclamation had officially outlawed slavery in Texas and the other states then in rebellion against the U.S. almost two and a half years earlier, and the defeat of the Confederate States Army in April 1865 allowed widespread enforcement of that to begin. But Texas was the most remote of the slave states, with a low presence of Union troops, so enforcement there had been slow and inconsistent before Granger’s announcement. Although Juneteenth is commonly thought of as celebrating the end of slavery in the United States, it was still legal and practiced in Union border states until December 6, 1865, when ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution abolished non-penal slavery nationwide.

Celebrations date to 1866, at first involving church-centered community gatherings in Texas. It spread across the South and became more commercialized in the 1920s and 1930s, often centering on a food festival. During the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, it was eclipsed by the struggle for postwar civil rights but grew in popularity again in the 1970s with a focus on African American freedom and arts.[11] By the 21st century, Juneteenth was celebrated in most major cities across the United States. Activists are campaigning for the United States Congress to recognize Juneteenth as a national holiday. Juneteenth is recognized as a state holiday or special day of observance in most of the 50 U.S. states.

The modern observance is primarily in local celebrations. Traditions include public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, singing traditional songs such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing”, and reading of works by noted African-American writers such as Ralph Ellison and Maya Angelou. Celebrations include rodeos, street fairs, cookouts, family reunions, park parties, historical reenactments, and Miss Juneteenth contests. The Mascogos, descendants of Black Seminoles, of Coahuila, Mexico, also celebrate Juneteenth.

History

End of slavery in Texas

During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. It was formally issued on January 1, 1863, declaring that all enslaved persons in the Confederate States of America in rebellion and not in Union hands were to be freed.

More isolated geographically, planters and other slaveholders had migrated into Texas from eastern states to escape the fighting, and many brought enslaved people with them, increasing by the thousands the enslaved population in the state at the end of the Civil War. Although most lived in rural areas, more than 1,000 resided in both Galveston and Houston by 1860, with several hundred in other large towns. By 1865, there were an estimated 250,000 enslaved people in Texas.

The news of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, reached Texas later in the month. The western army of the Trans-Mississippi did not surrender until June 2. On June 18, Union Army General Gordon Granger arrived at Galveston Island with 2,000 federal troops to occupy Texas on behalf of the federal government.[citation needed] The following day, standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Granger read aloud the contents of “General Order No. 3”, announcing the total emancipation of those held as slaves:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Although this event is popularly thought of as “the end of slavery”, the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to those enslaved in Union-held territory, who would not be freed until a proclamation several months later, on December 18, 1865, that the Thirteenth Amendment had been ratified on December 6, 1865. The freedom of formerly enslaved people in Texas was given legal status in a series of Texas Supreme Court decisions between 1868 and 1874.

Early celebrations

Formerly enslaved people in Galveston celebrated after the announcement. The following year, freedmen in Texas organized the first of what became the annual celebration of “Jubilee Day” on June 19. Early celebrations were used as political rallies to give voting instructions to newly freed slaves. Early independence celebrations often occurred on January 1 or 4.

In some cities, black people were barred from using public parks because of state-sponsored segregation of facilities. Across parts of Texas, freed people pooled their funds to purchase land to hold their celebrations. The day was first celebrated in Austin in 1867 under the auspices of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and it had been listed on a “calendar of public events” by 1872. That year black leaders in Texas raised $1,000 for the purchase of 10 acres (4 ha) of land to celebrate Juneteenth, today known as Houston’s Emancipation Park. The observation was soon drawing thousands of attendees across Texas; an estimated 30,000 black people celebrated at Booker T. Washington Park in Limestone County, Texas, established in 1898 for Juneteenth celebrations. By the 1890s Jubilee Day had become known as Juneteenth.

In the early 20th century, economic and political forces led to a decline in the Juneteenth celebrations. From 1890 to 1908, Texas and all former Confederate states passed new constitutions or amendments that effectively disenfranchised black people, excluding them from the political process. White-dominated state legislatures passed Jim Crow laws imposing second-class status. Gladys L. Knight writes the decline in the celebration was in part because “upwardly mobile blacks […] were ashamed of their slave past and aspired to assimilate into mainstream culture. Younger generations of blacks, becoming further removed from slavery were occupied with school […] and other pursuits.” Others who migrated to the Northern United States couldn’t take time off or simply dropped the celebration.

The Great Depression forced many black people off farms and into the cities to find work. In these urban environments, African Americans had difficulty taking the day off to celebrate. The Second Great Migration began during World War II, when many black people migrated to the West Coast where skilled jobs in the defense industry were opening up. A revival of Juneteenth began right before World War II began. From 1936 to 1951 the Texas State Fair served as a destination for celebrating the holiday, contributing to its revival. In 1936 an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 people joined the holiday celebration in Dallas. In 1938, Texas governor J. V. Allred issued a proclamation stating in part:

Whereas, the Negroes in the State of Texas observe June 19 as the official day for the celebration of Emancipation from slavery; and

Whereas, June 19, 1865, was the date when General Robert S. Granger, who had command of the Military District of Texas, issued a proclamation notifying the Negroes of Texas that they were free; and

Whereas, since that time, Texas Negroes have observed this day with suitable holiday ceremony, except during such years when the day comes on a Sunday; when the Governor of the State is asked to proclaim the following day as the holiday for State observance by Negroes; and

Whereas, June 19, 1938, this year falls on Sunday; NOW, THEREFORE, I, JAMES V. ALLRED, Governor of the State of Texas, do set aside and proclaim the day of June 20, 1938, as the date for the observance of EMANCIPATION DAY

in Texas, and do urge all members of the Negro race in Texas to observe the day in a manner appropriate to its importance to them.

Seventy thousand people attended a “Juneteenth Jamboree” in 1951. From 1940 through 1970, in the second wave of the Great Migration, more than five million black people left Texas, Louisiana and other parts of the South for the North and the West Coast. As historian Isabel Wilkerson writes, “The people from Texas took Juneteenth Day to Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and other places they went.” In 1945, Juneteenth was introduced in San Francisco by an immigrant from Texas, Wesley Johnson.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement focused the attention of African Americans on expanding freedom and integrating. As a result, observations of the holiday declined again (though it was still celebrated regionally in Texas). It soon saw a revival as black people began tying their struggle to that of ending slavery. In Atlanta, some campaigners for equality wore Juneteenth buttons. During the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign to Washington, DC, called by Rev. Ralph Abernathy, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference made June 19 the “Solidarity Day of the Poor People’s Campaign”. In the subsequent revival, large celebrations in Minneapolis and Milwaukee emerged as well as across the Eastern United States. In 1974 Houston began holding large-scale celebrations again, and Fort Worth, Texas, followed the next year. Around 30,000 people attended festivities at Sycamore Park in Fort Worth the following year. The 1978 Milwaukee celebration was described as drawing over 100,000 attendees.

Official recognition

In the late 1970s, the Texas Legislature declared Juneteenth a “holiday of significance […] particularly to the blacks of Texas”. It was the first state to establish Juneteenth as a state holiday under legislation introduced by freshman Democratic state representative Al Edwards. The law passed through the Texas Legislature in 1979 and was officially made a state holiday on January 1, 1980. Juneteenth is a “partial staffing” holiday in Texas; government offices do not close but agencies may operate with reduced staff, and employees may either celebrate this holiday or substitute it with one of four “optional holidays” recognized by Texas. In the late 1980s, there were major celebrations of Juneteenth in California, Wisconsin, Illinois, Georgia, and Washington, D.C.

In 1996 the first legislation to recognize “Juneteenth Independence Day” was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives, H.J. Res. 195, sponsored by Barbara-Rose Collins (D-MI). In 1997 Congress recognized the day through Senate Joint Resolution 11 and House Joint Resolution 56. In 2013 the U.S. Senate passed Senate Resolution 175, acknowledging Lula Briggs Galloway (late president of the National Association of Juneteenth Lineage) who “successfully worked to bring national recognition to Juneteenth Independence Day”, and the continued leadership of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation.

Activists are pushing Congress to recognize Juneteenth as a national holiday. Organizations such as the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation are seeking a Congressional designation of Juneteenth as a national day of observance.

In 2020, state governors of Pennsylvania, Virginia and New York signed an executive order recognizing Juneteenth as a paid day of leave for state employees.

Subsequent growth

Since the 1980s and 1990s, the holiday has been more widely celebrated among African-American communities, and has seen increasing mainstreaming in the US. In 1991 there was an exhibition by the Anacostia Museum (part of the Smithsonian Institution) called “Juneteenth ’91, Freedom Revisited”. In 1994 a group of community leaders gathered at Christian Unity Baptist Church in New Orleans to work for greater national celebration of Juneteenth. Expatriates have celebrated it in cities abroad, such as Paris. Some US military bases in other countries sponsor celebrations, in addition to those of private groups. In 1999, Ralph Ellison’s novel Juneteenth was published, increasing recognition of the holiday. By 2006, at least 200 cities celebrated the day.

Although the holiday is still mostly unknown outside African-American communities, it has gained mainstream awareness through depictions in entertainment media, such as episodes of TV series Atlanta (2016) and Black-ish (2017), the latter of which featured musical numbers about the holiday by Aloe Blacc, The Roots, and Fonzworth Bentley. In 2018 Apple added Juneteenth to its calendars in iOS under official US holidays. In 2020, several American corporations and educational institutions including Twitter, the National Football League, Nike, Harvard University, and Cornell University announced that they would treat Juneteenth as a company holiday, providing a paid day off to their workers, and Google Calendar added Juneteenth to its US Holidays calendar.

In 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the worldwide protests sparked by the police killing of George Floyd, a controversy ensued when it emerged that Donald Trump had scheduled his first political rally since the pandemic’s outbreak for Juneteenth in an arena in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was the site of the 1921 race massacre in the Greenwood district. In response to the controversy, the rally was rescheduled for the following day. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Trump said, “I did something good: I made Juneteenth very famous. It’s actually an important event, an important time. But nobody had ever heard of it.”

Recognition

Recognition of Juneteenth varies across the United States. It is not recognized by the federal government. Most states recognize it in some way, either as a ceremonial observance or a state holiday; some designate it as a paid day off or state employees. Some cities have recognized it through proclamation, and a variety of employers have policies allowing employees to take the day off.

After Texas recognized the date in 1980, many states followed suit. By 2002, eight states officially recognized Juneteenth and four years later 15 states recognized the holiday. By 2008, nearly half of US states observed the holiday as a ceremonial observance. The only four states yet to legally recognize Juneteenth as either a state or ceremonial holiday are Hawaii, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana. Governor Kristi Noem of South Dakota proclaimed June 19, 2020, as Juneteenth Day, spurring calls for it to be recognized annually, rather than just for 2020. Similarly, Gov. Doug Burgum, R-ND, announced that the state would formally recognize Friday, June 19, 2020, as Juneteenth Day in North Dakota for the year 2020. Although there has been no statewide call for observance of the holiday in Hawaii, Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell announced that Honolulu City Council committee passed Resolution 20-154, proclaiming June 19, 2020, as “Juneteenth” and an annual day of honor and reflection going forward for the City and County of Honolulu.

Celebrations

The holiday is considered the “longest-running African-American holiday” and has been called “America’s second Independence Day”. It is often celebrated on the third Sunday in June. Historian Mitch Kachun considers that celebrations of the end of slavery have three goals: “to celebrate, to educate, and to agitate”. Early celebrations consisted of baseball, fishing, and rodeos. African Americans were often prohibited from using public facilities for their celebrations, so they were often held at churches or near water. Celebrations were also characterized by elaborate large meals and people wearing their best clothing. It was common for former slaves and their descendants to make a pilgrimage to Galveston. As early festivals received news coverage, Janice Hume and Noah Arceneaux consider that they “served to assimilate African-American memories within the dominant ‘American story’. ”

Observance today is primarily in local celebrations. In many places, Juneteenth has become a multicultural holiday. Traditions include public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, singing traditional songs such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing”, and reading of works by noted African-American writers such as Ralph Ellison and Maya Angelou. Celebrations include picnics, rodeos, street fairs, cookouts, family reunions, park parties, historical reenactments, blues festivals and Miss Juneteenth contests. Strawberry soda is a traditional drink associated with the celebration. The Mascogos, descendants of Black Seminoles, of Coahuila, Mexico also celebrate Juneteenth.

Juneteenth celebrations often include lectures and exhibitions on African-American culture. The modern holiday places much emphasis on teaching about African-American heritage. Karen M. Thomas wrote in Emerge that “community leaders have latched on to help instill a sense of heritage and pride in black youth.” Celebrations are commonly accompanied by voter registration efforts, the performing of plays, and retelling stories. The holiday is also a celebration of soul food and other food with African-American influences. In Tourism Review International, Anne Donovan and Karen DeBres write that “Barbecue is the centerpiece of most Juneteenth celebrations”.

Look for Juneteenth celebrations here on Harlem World Magazine.

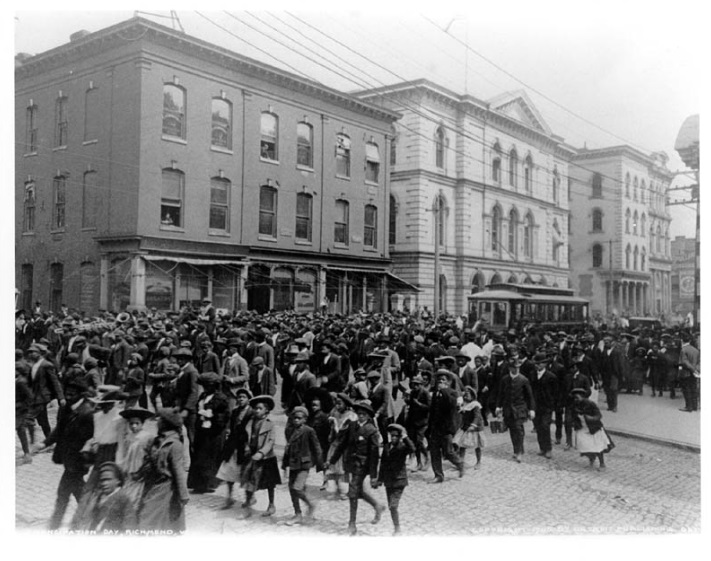

Photo credit: 1) An early celebration of Emancipation Day (Juneteenth) in 1900. 2) General Order No. 3, June 19, 1865. 3) Emancipation Day celebration in Richmond, Virginia, 1905. 4) Seitu Oronde 2016. 5) Google video.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Harlem World Magazine, 2521 1/2 west 42nd street, Los Angeles, CA, 90008, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact