Have some fews and two? Put it in your kick, head to the nearest frolic pad, and prove that you’re a jitterbug.

Have some fews and two? Put it in your kick, head to the nearest frolic pad, and prove that you’re a jitterbug.

If these phrases sound like gibberish, you must not be hep—or at least you haven’t read the [easyazon_link identifier=”B01FZ4UAZU” locale=”US” tag=”harlemworld-20″]Hepster’s Dictionary,[/easyazon_link] a glossary of Harlem jive that is thought to be the first dictionary written by an African American.

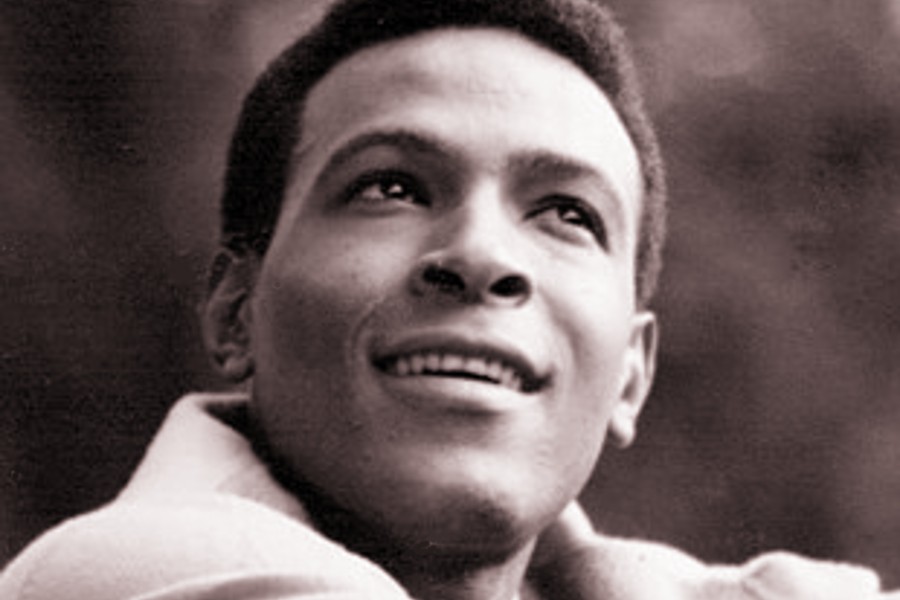

The 1938 dictionary was the work of Cab Calloway, the influential bandleader and jazz legend known as the “Hi De Ho” man. His small book didn’t just document a moment in Harlem’s vibrant history—it helped introduce African American slang to white America. The language it helped preserve still lives on in American English, in terms like boogie-woogie, “come again?”, zoot suit, and even hep (now hip).

The book was little more than a slender pamphlet, but one with deep roots. In the early 20th century, the growing popularity of jazz coincided with the Great Migration, a movement of African Americans from the South to Northern cities. As black people headed to urban areas in search of new opportunities, Harlem became a growing center of African American music and culture.

The Cotton Club, in particular, was a hub for black jazz musicians in search of their big break. Though open to white audiences only, it became a place in which African American jazz artists like Duke Ellington and Count Basie found fame. Cab Calloway, with his distinctive scat singing style, was among its most recognizable stars. Throughout a decades-long career, Calloway became known for songs—like “Minnie the Moocher”—that were peppered with the vocabulary that later made its way into his dictionary.

Born in 1907, [easyazon_link identifier=”B06X9KWYHP” locale=”US” tag=”harlemworld-20″]Cabell Calloway[/easyazon_link] had been performing in jazz clubs since he was a teenager. Privately trained in vocal and musical performance, he defied his parents’ classical expectations and turned to jazz instead, performing in all-black revues with his sister, an accomplished bandleader. Soon, Calloway was a bandleader himself, earning a permanent slot at the Cotton Club, which led to national prominence.

Harlem was in the midst of a black cultural renaissance. And it was full of slang. Jazz musicians like Calloway talked jive, a kind of shorthand that turned ordinary conversation into an extended jazzy riff. Like jazz, jive talk was colorful, improvisational and rhythmic. It was also a matter of survival, writes language historian Herbert L. Foster. Though it was spoken in public, it was a way for African Americans to communicate privately—a kind of linguistic rebellion that was as serious as it was humorous.

Calloway, who spoke jive with his band, began to incorporate the phrases into his songs. Though his music remained popular, by the late 1930s he could see the writing on the wall. White swing musicians were taking over the jazz music black artists had pioneered, bringing it into the mainstream and profiting. As a result, black musicians were being pushed aside. In order to stay relevant, Calloway turned to jive.

Along with his manager, Calloway compiled a short pamphlet that translated jive talk for less hip audiences. “The little book provided hours of harmless fun with readers who had seldom if ever heard Harlem street slang spoke in real life,” writes biographer Alyn Shipton.

The book—believed to be the first dictionary authored by an African American—turned fans into insiders. It was so popular that seven volumes were published, and Calloway even appeared as a kind of hepster professor in some of his performances. It was hugely successful with both black and white audiences, introducing jive talk and Harlem-style jazz to people who lived far from New York.

Related articles

- Castillo’s World: The Best Spots To Enjoy Harlem Nightlife (harlemworldmag.com)

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Harlem World Magazine, 2521 1/2 west 42nd street, Los Angeles, CA, 90008, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact