Following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, 52nd Street replaced 133rd street as “Swing Street” of the community of Harlem.

Following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, 52nd Street replaced 133rd street as “Swing Street” of the community of Harlem.

133rd Street is a street in Harlem and the Bronx, New York City.

In Harlem, Manhattan, it begins at Riverside Drive on its western side and crosses Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue, and ends at Convent Avenue, before resuming on the eastern side, crossing Seventh Avenue, and ending at Lenox Avenue.

In Port Morris in the Bronx, it runs from Bruckner Boulevard/St. Ann’s Place to Locust Avenue.

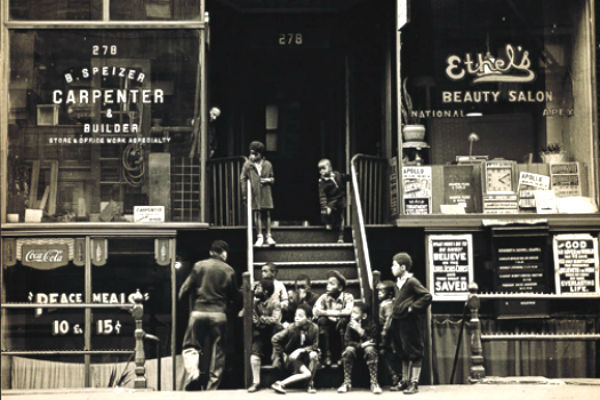

The block between Seventh Avenue and Lenox Avenues was once a thriving nightspot, known as “Swing Street”, with numerous cabarets, jazz clubs, and speakeasies.

The street is described in modern times as “a quiet stretch of brownstones and tenement-style apartment houses, the kind of block that typifies this section of central Harlem.”

History

The street has historical significance during the Prohibition era when there were many speakeasies operating on the street and it was known as “Swing Street”.

The street also gained a reputation as “Jungle Alley” because of “inter-racial mingling” on the street.

During the Jazz Age there were at least 20 jazz clubs on the street, mainly concentrated between Lenox Avenue (Malcolm X Boulevard) and Seventh Avenue, and a young Billie Holiday performed here and was discovered here at the age of 17.

Holiday has cited 133rd Street as the original Swing Street, playing a major role in the development of African-American entertainment in Harlem and jazz.

The Nest Club opened in 1923 when Melville Frazier and John Carey leased the building at 169 West 133rd Street and established the Barbecue Club on the main floor and The Nest on the downstairs floor, which opened on October 18, 1923.

Nightclubs of note include Tillie’s Chicken Shack, known for torch singer Elmira, Bank’s Club, Harry Hansberry’s Clam House at 146 W. 133rd St., one of New York City’s most notorious LGBT speakeasies established in 1928, featuring Gladys Bentley in a tuxedo singing “her own risque lyrics to popular songs”, and Catagonia Club, better known as Pod’s and Jerry’s, which featured Harlem Stride style inventor, jazz pianist and composer Willie “The Lion” Smith.

The street began to lose its attraction following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, and the Harlem Riot of 1935 effectively killed the reputation of the street as a racial safe haven, and most of the interracial clubs were forced to close.

This was a time of style before the Zoot suit when men dressed in style with long Chesterfield coats with velvet collars and gloves, brimmed hats, dress shoes, and ties.

One of the last clubs to stay open was Pod’s and Jerry’s, which was renamed “The Log Cabin” in 1933, and stayed open until about 1948-9, long after 52nd Street had replaced 133rd Street as the “Swing street”.

The Walt Whitman Blog / Transnational Poetry reports that in Langston Hughes’ Not a Movie, he paints a romantic vision of New York City by talking about an African American’s journey in escaping the south, crossing the Mason Dixon Line, and not stopping until he reached 133rd Street. The first stanza says, “and he got the midnight train/ and he crossed that dixie line/now he’s livin’/on a 133rd” (396).

Hughes represents 133rd Street in New York City as the ultimate goal toward freedom as well as a chance at happiness, something that probably seemed impossible to the African American living in the south.

Hughes’ words about New York evoke similar feelings as Whitman does in poems like Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, recognizing New York as a place of a universal community, (as I discussed in a previous post).

Hughes might have even been playing on Whitman’s Crossing Brooklyn Ferry when the character in Not a Movie is “crossing” the Mason-Dixon line.

Hughes mentions 133rd street as the hopeful destination twice in this poem, and after a little research, I learned that anyone who was a part of the Harlem Renaissance recognizes 133rd street as the “original swing street, ”although the more well-known street during the Harlem Renaissance was 52nd. An article called “The Rise and Fall of the Original Swing Street” in the New York Press notes.

Billie Holiday said, “133rd St. was the real swing street, like 52nd St. later tried to be… 133rd St. would always be the genuine article, even after it seemed everyone else had forgotten it ever existed.”

The character in Not a Movie wanted more than anything to reach 133rd street, what must have seemed like heaven on earth; music, alcohol, dancing, friends, and (relative) freedom.

Landmarks

Numerous mills sprang up along the street on the eastern side but many of the former derelict buildings have been razed to the ground and new buildings erected.

The New York Post has a printing center here. On the western side is the Terence D. Tolbert Educational Complex and Roberto Clemente School, KIPP Infinity Charter School, and the Manhattanville Bus Depot.

The New York Structural Biology Center is situated in the Park Building at 89 Convent Avenue opposite the street.

On the eastern side is Bethlehem Moriah Baptist Church and Bill’s Place, a jazz club established in 2006 by tenor saxophonist Bill Saxton in a building which was the former speakeasy Tillie’s Chicken Shack.

Bishop R.C. Lawson once had a Bible book store on 133rd Street.

Today

Swing Street no longer exists, but the attitude still exists.

Photo credit: 1) Strolling gents Swing Street. 2) Kids on Swing Street.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Harlem World Magazine, 2521 1/2 west 42nd street, Los Angeles, CA, 90008, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact